The Rise and Importance of Blockchain Technology in The Luxury Fashion Industry

- solveiga toffolo

- Mar 22, 2022

- 6 min read

Updated: Apr 1, 2023

A look into the ways in which this revolutionary technology could aid to transform the element of transparency in luxury supply chains and its role in CRS:

For luxury companies around the globe, meeting the evolving demands of consumers has been a tough battle to conquer, especially in the hypercompetitive market of the present day. As millennials and generation Z consumers make up ‘85% of the global luxury sales growth’ and 60% of them are driven by environmental and ethical concerns when shopping, it comes to no surprise that luxury companies are turning to technology for a solution (Kemp, 2020). The pandemic has sped up a phenomenon that was already in preparation; a wish for the fashion industry to wake up to the demands of sustainability and ethical sourcing. Subsequently, luxury conglomerates such as LVMH, have already begun to incorporate blockchain technology into their supply chain process.

Image credits: Marguerite Bornhauser

In this text we will discuss the breadth of opportunities that lie ahead for the fashion industry, including trackable supply chains and combating the sale of inauthentic goods. Hand in hand, the two can create an army of solutions to the problems consumers care most about, transparency and truth (Cernansky, 2021). However, like with any new technology, there are an array of possible threats and disruptions. This text will specifically analyze that although blockchain may be used going forward, it may be harder to implement for past luxury production.

First and foremost, it is essential to define what blockchain technology is and how it functions. In essence, the blockchain operates as, ‘... a distributed, shared, encrypted database that serves as an irreversible and incorruptible public storage of information.’ (Shlomit & Monroy, 2020). It allows virtually anything of value to be exchanged with other entities freely and immutably with no intermediary. Smart contracts, which are a virtual set of conditions recorded in code, also run on blockchain technology, where such data is stored in blocks that are then linked to the next block and remain forever on the public ledger (CFI, 2021). In the fashion industry, smart contracts, which require no paperwork and are secure due to the difficulty to hack a block, could potentially be used to process payments to suppliers and make certain, for both companies and buyers, that workers are paid fairly, for example. This way, brands can create a permanent record of all the steps a garment goes through when being produced, from its material composition to providing information on the working condition of those creating it (Kemp, 2020).

As founder of Blockchain Peter Smith stated in a Business of Fashion (BoF) interview, blockchain acts as a “distributed way of securing truth” and it seems as though it is here to stay, as the revolutionary protocol has already given birth to countless opportunities and fashion blockchain-based startups (Baskin, 2018). Take as an example the platform Aura. Established by LVMH in collaboration with Microsoft and blockchain software company Consensys, the blockchain system enables consumers to trace the origin and lifecycle of their purchases (Zhao, 2021). Not only will such a technology aid in individualizing each garment and making its creation process transparent to consumers, but could also allow tackling the spread of inauthentic luxury pieces. This issue is one that all luxury houses face and can be highlighted by the fact that in 2020, the annual sale loss from counterfeiting in the industry reached a total of, ‘26.3 billion euros.’, not only harming business revenues, but also the environment (Statista, 2021).

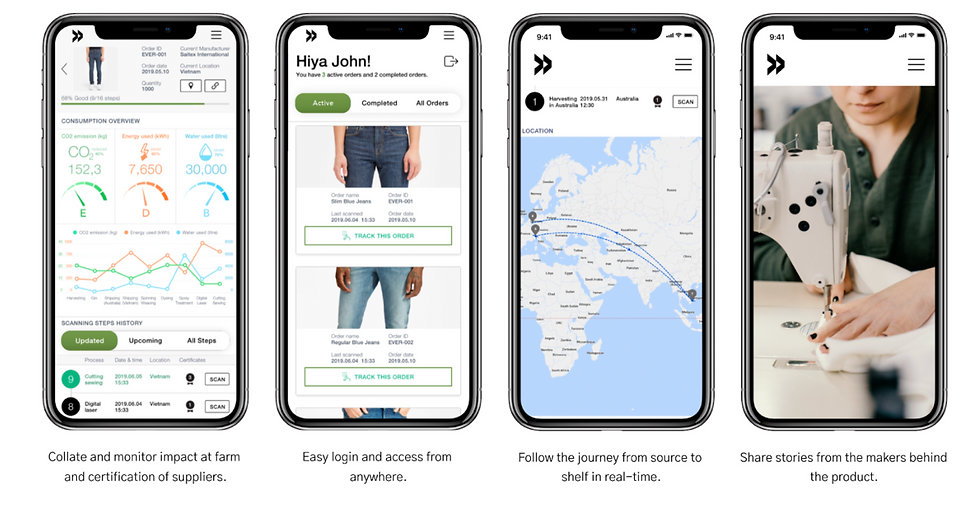

Another way in which startups have been able to aid in making the production process more transparent and thus more sustainable, is through going as far as incorporating blockchain technology in the fibers of the product itself. For example, recent startup FibreTrace has come up with a groundbreaking method of tracing production. The way it works rests in the bioluminescent ceramic pigment, fine as dust, that is added to the fibers of the material that make up the individual garment. Each ‘batch’ of pigment is unique, resembling almost an original serial code. Progressively, through each step in the supply chain, the fiber is scanned and information on it is added and secured on a blockchain, subsequently made publicly available (see Fig 1. for FiberTrace’s supply-chain process) (Bauck, 2021).

Fig 1. (FibreTrace, 2021)

It is also worth mentioning that not only businesses have partaken in the development of blockchain technologies in the fashion industry, but governments are also starting to intervene. For example, in Italy, the development of blockchain is seen as an opportunity to protect the title of ‘Made in Italy’ in the textile sector. In 2019, the Italian Ministry of Economic Development in partnership with several other European governmental entities and with the financial aid of the European Commission has established an initiative titled, “Transparency and Traceability for Sustainable Textile and Leather Value Chains”. It aims to identify the opportunities and advantages of blockchain, in order to safeguard the authenticity and intellectual property of luxury houses that make up the nation’s most prized industry (Bernardino, 2019).

Although for this industry blockchain technology poses more advantages than risks, it should be strongly argued that the use of blockchain technology is not one hundred percent bulletproof from risks. As the technology still lies in its infancy and methods such as smart contracts grow in popularity, companies should remain vigilant on what regulations may be adopted from legal systems around the world. Additionally, due to its decentralized nature, businesses should be cautious when utilizing blockchain technology, as any eventual risks generated from agreements made via smart contracts will lay solely in the hands of both parties involved (Deloitte, 2021).

In addition, it is essential to note that companies in the luxury sector should not solely rely on blockchain looking forward. This comes as, during the pandemic, the demand for second-hand luxury goods (used garments) increased exponentially, whilst the demand for first-hand (new garments) declined (see Fig 2).

Fig 2. Buoyant second-hand luxury goods market, (Biondi, 2021)

Although this trend comes as no surprise due to consumers’ decreased purchasing power amidst the pandemic, what is important to highlight is that when it comes to previously owned or antique pieces of clothing, only a human is able to produce a truthful statement on its authenticity and provenance (Barua, 2021). Similarly, Claudia D’Arpizio, partner at Bain & Company, believes that despite the promise of blockchain, sees humans remaining at the core of the authenticating profession (Biondi, 2021).

In conclusion, if this trend continues, blockchain may not remain as pertinent as we may believe in the luxury fashion and retail sector. However, in the realm of newly produced collections of luxury goods, it is clear that blockchain technology and smart contracts have a plethora of advantages that can aid through the entirety of a goods production process. For this reason, companies should opt to continue implementing and gaining knowledge on the endless possibilities of blockchain technology, in order to satisfy changing customer needs and expectations. In essence, the blockchain system will be able to act as a wake-up call and a way for the industry to rethink its values to provide for a more sustainable, ethical, and transparent supply process, which has seen no other technology as effective in tackling the issue so far.

Reference List:

Barua, A. (2021, June). A spring in consumers’ steps: Americans prepare to get back to their spending ways. Deloitte Insights. https://www2.deloitte.com/us/en/insights/economy/us-consumer-spending-after-covid.html

Baskin, B. (2018, Nov 30). Blockchain Explained: Ken Seiff and Peter Smith. BoF. https://www.businessoffashion.com/videos/technology/blockchain-explained-ken-seiff-peter-smith-rohan-silva-cryptocurrency/

Bauck, W. (2021, March 13). Tracing a garment: industry looks to shine light on its blind spots. Financial Times. https://www.ft.com/content/686619d4-e910-470b-b8e2-8d2bca269f96

Biondi, A. (2021, Oct 2). The luxury authenticators who keep fakes out of buyers’ hands. Financial Times. https://www.ft.com/content/73afdaa5-1e95-4a93-8f37-20a887a7feb8

Cernansky, R. (2021, July 1). Consumers want labour rights transparency. Fashion is lagging. Vogue Business. https://www.voguebusiness.com/sustainability/consumers-want-labour-rights-transparency-fashion-is-lagging

CFI. (2021). What are smart contracts? CFI. https://corporatefinanceinstitute.com/resources/knowledge/deals/smart-contracts/

Deloitte. (2021). Risks posed by blockchain-based business models. Deloitte. https://www2.deloitte.com/us/en/pages/risk/articles/blockchain-security-risks.html

Di Bernardino, Claudia. (2019). Blockchain technology in the fashion industry: opportunities, applications, and challenges. CMP Law. https://www.cmplaw.it/wp-content/uploads/2019/12/Blockchain-technology-.pdf

FibreTrace. (2021). Our Technology. FibreTrace. https://www.fibretrace.io/technology

Shlomit, Y & Monroy, G. (2020, April 8). WHEN BLOCKCHAIN MEETS FASHION DESIGN: CAN SMART CONTRACTS CURE INTELLECTUAL PROPERTY PROTECTION DEFICIENCY?. SSRN. https://ssrn.com/abstract=3488071

Statista. (2021). Sales losses from counterfeit goods worldwide in 2020, by retail sector. Statista. https://www.statista.com/statistics/1117921/sales-losses-due-to-fake-good-by-industry-worldwide/

Zhao, K. (2021, Aug 10). The Devil Wears Pixels: 8 landmark moments in fashion’s NFT revolution—and what comes next. Vogue. https://vogue.sg/fashion-nft-revolution/

Comments